Archduke Joseph of Austria (Palatine of Hungary)

| Archduke Joseph of Austria | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palatine of Hungary | |||||

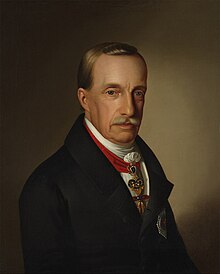

Portrait by Miklós Barabás (1846) | |||||

| Born | 9 March 1776 Florence, Grand Duchy of Tuscany | ||||

| Died | 13 January 1847 (aged 70) Buda, Kingdom of Hungary | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouses | |||||

| Issue |

| ||||

| |||||

| House | Habsburg-Lorraine | ||||

| Father | Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor | ||||

| Mother | Maria Luisa of Spain | ||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | ||||

| Signature |  | ||||

Archduke Joseph Anton of Austria (German: Erzherzog Joseph Anton Johann Baptist von Österreich; Hungarian: Habsburg József Antal János Baptista főherceg, József nádor; 9 March 1776 – 13 January 1847) was the 103rd and penultimate palatine of Hungary who served for over fifty years from 1796 to 1847, after a period as governor in 1795.

The latter half of his service coincided with the Hungarian Reform Era, and he mediated between the government of Francis I, King of Hungary and Holy Roman Emperor and the Hungarian nobility, representing the country's interests in Vienna. He played a prominent role in the development of Pest as a cultural and economic centre; the neoclassical buildings constructed on his initiative define the city's modern appearance. The landscaping of the City Park of Budapest and Margaret Island happened under his supervision. He supported public education, technical higher education, the arts, the construction of railroads, and various progressive-thinking societies and associations. He donated substantially towards the establishment of the Hungarian National Museum, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, and the National Széchényi Library.

He was an archduke of Austria and a prince of Bohemia, Hungary, and Tuscany as the son of Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor. The Hungarian or Palatinal branch of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine descends from him. In the Imperial Army, and later in the Austrian Army, he bore the rank of Feldmarschall.

Early life and education[edit]

Childhood in Tuscany[edit]

Archduke Joseph Anton Johann Baptist of Austria was born on 9 March 1776 in Florence, Grand Duchy of Tuscany as the ninth child and seventh son of Leopold I, Grand Duke of Tuscany and Infanta Maria Luisa of Spain.[1][2] He had fifteen siblings, two of whom died in infancy. Through his father, he was a grandson of Maria Theresa, Holy Roman Empress Dowager, Queen Regnant of Bohemia and Hungary.[1] The family lived in the Palazzo Pitti in Florence, spent summers in the Villa del Poggio Imperiale or the Villa di Poggio a Caiano, and some winters in Pisa.[3]

The grand ducal couple created a warm, intimate environment for their children. They raised them according to the modern principles of the age, paying special attention to their diet and regular physical exercise. Their education plan was based both on traditional courtly values, emphasising etiquette and royal duty, and on the newer ideas of John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[4] Until they turned four, the children were entrusted to an all-female staff composed of German-, Italian-, and French-speaking women who were only allowed to use their respective mother tongues with them. Instruction in reading and writing started at the age of three, and regular language classes a year later.[5] According to the desires of the children's grandmother, Empress Dowager Maria Theresa, the family's life revolved around the strict observance of Catholic rituals. Every day, the children listened to religious texts while getting ready in the morning, attended mass, studied the catechism, and prayed the rosary. The Empress followed their development closely through her correspondence with their parents and educational staff.[6]

It was Maria Theresa who appointed the young archdukes' ajo, 'governor', Count Franz de Paula Karl von Colloredo-Waldsee, assisted by the sottoajo, 'vice-governor', Major Marquess Federigo Manfredini, and tutors.[7] Grand Duke Leopold and Count Colloredo aimed to teach the children to lead a simple life, be humble, dutiful, and devoted to the well-being of their subjects. In their studies, they were taught to be inquisitive and independent.[7] The Grand Duke wished for his children to live as free and unrestricted as possible, while the ajo expected them to be graceful, serious, and disciplined beyond their years, leading to disagreements.[8] Archduke Joseph was only under Colloredo's guidance for two and a half years, and when he left in 1782, Major Manfredini was promoted to ajo. He allowed his charges more freedom.[9][10]

The preparatory stage of Joseph's education lasted until the age of nine, by when he had learned to speak and write in German, French, Italian, and Latin.[5][10] He received the traditional education of Austrian archdukes, learning etiquette and conduite (the behaviour expected in high society), genealogy, geography, history, ethics, law, natural law, political science, and mathematics.[5] Joseph had a preference for history, archaeology, and natural history,[11] and was not as apt in mathematics.[10] It was important for his parents that all of their children learned some form of manual labour; Joseph was instructed in gardening, botany, and horticulture.[11] He learned the binomial nomenclature and taxonomy of over six thousand plants.[10]

The teacher to have the greatest impact on the children was Count Sigismund Anton von Hohenwarth,[11] an ex-Jesuite[12] who later became prince-archbishop of Vienna.[11] His pedagogical philosophy was based on Enlightenment ideas, and he taught the archdukes that a person's ‘true vocation’ was to strive for the happiness of themselves and others, which could only be achieved in a society. He analysed with them examples of good and bad statesmanship, focusing on the importance of institutions, legislation, education, the sciences, the arts, and different aspects of the economy. He taught them to objectively assess all matters.[13]

Youth in Vienna[edit]

Archduke Joseph's father, Grand Duke Leopold, was heir presumptive to the thrones of his brother, Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, who had no surviving children. When he died in 1790, Leopold and his family moved to Vienna,[2][14] where Joseph and his brothers arrived on 13 May. With his approaching fifteenth birthday, the final, three-year stage of his education started. Focused on military training and political science, this included subjects such as politics, investigative history, and law, which he learned from Hofrat ('Court Councillor') Franz von Zeiller. He and his brothers travelled extensively and inspected institutions, recording their experiences in diaries.[14]

First visit to Pest-Buda[edit]

In 1792, sixteen-year-old Joseph lost both of his parents in three months, and his eldest brother, Francis, became emperor-king. Joseph accompanied him to his coronations in Frankfurt, Prague, and Buda, where he spent twenty-seven days. This was his first visit to Pest-Buda,[2][15] and he went to see the library, botanical garden, and natural history collection of the Royal University of Pest (today Eötvös Loránd University). He met leaders of the country, spending the most time with the Prince-Primate, József Battyhány, Prince-Archbishop of Esztergom, but also seeing Judge Royal Károly Zichy and Chancellor Károly Pálffy. He preferred Pest to Buda.[15]

Visit to the Austrian Netherlands[edit]

In 1794, Joseph went on on a trip to the Austrian Netherlands, which the Habsburg monarchy had temporarily regained during the French Revolutionary Wars. After his brother's swearing-in in Brussels, he studied the culture and economy of the country. From 14 April to 31 May, he was on the battlefield and witnessed one minor win and multiple losses. He analysed the tactics of the Imperial Army and the French Revolutionary Army, and drew caricatures of imperial military leaders.[16]

Death of Archduke Alexander Leopold[edit]

When Joseph's father became king of Hungary in 1790, he re-established the office of palatine (Hungarian: nádor), which had been vacant since 1765. The Diet of Hungary elected one of his younger sons, fourth-born Archduke Alexander Leopold.[17] In 1795, he uncovered and repressed a conspiracy by the Hungarian Jacobin movement led by Ignác Martinovics. He then joined his family for a holiday in Laxenburg castles, where he planned to surprise his younger sister Amalia with a display of fireworks on her name day. As an enthusiastic pyrotechnician, he prepared the explosives himself.[17][18]

On 10 July, the day of the planned festivities, between 12 and 1 p.m., something caught fire, causing all of the prepared rockets and the remaining gunpowder to explode. His brother Charles rushed to the rescue with servants, but they struggled to break down the door. This delay was probably what led to Alexander Leopold's death.[17] He was found lying unconscious on the floor, his neck, back, and arms covered in burns from his clothes that had caught fire. He soon regained conscience and lived another forty hours in agony, before passing away on 12 July.[17][18]

Governor of Hungary[edit]

Background[edit]

The death of Alexander Leopold was greatly mourned by progressive Hungarian nobles, who had hoped that he would help them establish a constitutional monarchy. Conspiracy theories emerged that he had been murderd by the Viennese court for planning to seize the crown with the help of Judge Royal Zichy.[19] A crown guard, Count József Teleki, főispán of Békés and Ugocsa Counties advised the King to allow for the election of another member of the imperial family to calm tensions. Moson County proposed Albert, Duke of Teschen, the King's uncle-in-law, who had served as governor of Hungary from 1765 to 1781. Others would have preferred Archduke Charles, who had become popular with his military successes in the French Revolutionary Wars, and Count Teleki himself suggested Joseph. Although on 18 July Emperor-King Francis asked for more time to prepare an election, on the 20th[20] he appointed Joseph governor of Hungary.[21][22]

The appointment of a governor instead of the election of a palatine was an important win for the reactionary party of the Hungarian nobility led by Baron József Izdenczy, and seen by others as a step back on the road of constitutional development.[23] Izdenczy's circles had painted a grim picture of Hungary to the King, convincing him that a rebellion was imminent. Francis decided that he would not call for a diet because of the Martinovics uprising, and Izdenczy's party also hoped to abolish the office of palatine. Nevertheless, to avoid upsetting progressive circles, the Baron advised the King to give more power to Joseph than that of the previous governor, so that his position would be more similar to that of a palatine.[24] Thus, Joseph was not welcomed with unequivocal enthusiasm, especially because many of the holders of the highest Hungarian public offices were replaced at the same time, signalling a possible regime change.[25]

Before he was sent to Buda, the new governor received an education in Hungarian law from the Josephinist canon lawyer György Zsigmond Lakics,[11][20] recommended by Izdenczy.[26] He also received instructions from King Francis who advised him to ‘keep [his] house in order, manage it well, [...] treat [his] entourage humanely and [not to] tolerate intrigue’. His brother suggested that Joseph travel around Hungary to get to know his new subjects while avoiding spending too much money on this tour. He reminded him that his first duty would be justice to his people.[11]

Archduke Joseph entered Buda on 19 September 1795, heading a procession under triumphal arches, received by a cheering crowd.[11][20] On the 21st, he was inaugurated as főispán of Pest-Pilis-Solt-Kiskun County, followed by mass in the Matthias Church, a lunch hosted by Prince-Primate Battyhány with six hundred guests, and a ball at night.[11] On the next day, he took his seat as president of the governing council.[11] He continued studying Hungarian history and law with Lakics,[11][20] and started learning the language from Ferenc Verseghy who had participated in the Hungarian Jacobin movement.[2]

You are to stand at the helm of a noble and powerful nation, of a great and rich country, whose powers must still be increased for the sake of the dynasty. Let it be your main goal to win the respect, confidence, and love of this nation, and work for it with all your might! The Hungarian is very fiery and very sensitive in his privileges, besides being distrustful, but by a strict observance of our laws one can easily get along with him.

— Emperor-King Francis, letter to Archduke Joseph on his governorship in Hungary

Work as governor[edit]

The first issue Joseph needed to settle was the case of eight university and secondary school teachers who had allegedly been associated with Imre Martinovics and freemasonry. The accusations were one of them translating La Marseillaise to Hungarian, and others organising gatherings with convicted freemasons and Martinovics co-conspirators[27] or teaching pantheism.[28] The King ordered an investigation, which was not in the interest of János Németh, head of the Royal Directorate and close ally of Izdenczy, as he lacked proof. He persuaded Joseph to propose to the King the dismissal of five of the accused teachers, which Francis accepted.[29] According to Domanovszky, in this first matter, which he had to solve three weeks after arriving in Buda, the Governor did have a mind of his own and relied entirely on a referral he had received from Németh.[29]

The other important matter in Joseph's first year in Hungary was that of the Royal University of Pest. Since 1790, there had been plans to move it to a smaller city, namely Nagyszombat (today Trnava, Slovakia), Esztergom, Vác, or Eger.[29] In 1794, these cities urged their respective counties to reach an agreement, while Pest tried to keep the institution. Most of the clerical elite, conservative aristocrats, and the gentry's deputies wanted to see it removed.[30] On 23 October 1795, the referral reached the governing council. The Governor himself followed public opinion.[31]

The first problem Joseph resolved on his own was an outbreak of plague in Syrmia County, worsened by hurried and inconsistent countermeasures. Joseph ordered a lockdown of the infected area with a cordon sanitaire guarded armed civilians from nearby uninfected villages under military supervision. This lead to a revolt in two villages, who let out their quarantined neighbours and attempted to break through the cordon.[31] The Governor appealed for an arms shipment to the martial council in Vienna, which generally opposed arming civilians in fear of a rebellion. Joseph negotiated and obtained the necessary weapons, preventing the disease from spreading to other parts of the country.[32]

The King mainly tasked Joseph with policing dissenters and uncovering suspected conspiracies.[31] In smaller debates on religious tolerance (which he supported despite being a devout Catholic),[33] wine export (which he supported),[34] or giving refuge to French priests (which he refused to do as he feared that they would be too much of a burden and keep local priests from advancing in their careers),[35] he proved to be a level-headed and caring leader.[34]

Palatine of Hungary[edit]

Palatinal election[edit]

Contrary to the hopes of the reactionary party, most members of the aristocracy and the gentry wanted to see Archduke Joseph as elected palatine, a sentiment that was only strengthened after they met him.[36] However, the body to elect the palatine was the Diet of Hungary, which Emperor-King Francis had no intention of allowing to happen. [36] As he needed the assistance of Hungarians in fighting the French Revolutionary Wars[37] he was eventually convinced to gather a diet with the sole purpose of electing a palatine.[38] After much negotiation, during which the Governor tried to convince the King that a diet and a palatine were necessary to attain the required aid, while Izdenczy argued against him,[39] Francis conceded to Joseph.[36] On 8 November 1796, the diet had its first session in Pozsony (today Bratislava, Slovakia),[11] Archduke Joseph was elected palatine on 12 November[40][41] and inaugurated on the 14th.[11][42]

Work as palatine[edit]

1796–1802[edit]

After his election as palatine, Joseph assumed a more active role in Hungary. While previously he had mostly relied on the opinions and decisions of Izdenczy's ultra-conservative party and supported the removal of progressive teachers accused of corrupting the youth,[29] he now realised that their investigation lacked proof and was not properly conducted. He criticised this to the Viennese court and reprimanded Németh.[43]

Economic considerations first appeared in Archduke Joseph's letters in early 1796. In early February, he alerted Emperor-King Francis to the devastation that the loss of the Polish market for Hungarian wine caused after Poland had been partitioned twice. His proposal that the Emperor-King should help out wine trade was his first individual idea,[44] but was rejected as Vienna wanted to maintain the economic dominance of the Habsburg hereditary lands.[45] In early September, while the sovereign continued to demand soldiers and ammunition from Hungary for the ongoing war, the Palatine relayed the nobility's wish for another diet, which was fervently opposed by the court.[46] This might have convinced Joseph that Vienna was partial against Hungary and that many of their decisions were biassed.[47]

During these first years of his palatinate, the majority of the Archduke's time was taken up by war preparations, equipping and training Hungarian soldiers. In early 1797, after military failures, Emperor-King Francis sent his family to Buda for their safety.[48] Around this time, a shift can be observed in the tone of the letters exchanged by the brothers: Joseph stopped merely executing Francis' will and became the more pro-active party.[48] He remained a conservative and worried that the ideas of Enlightenment thinkers could ‘confuse’ the less-educated. He warned the Emperor to keep an eye on returning prisoners of war who might have picked up revolutionary ideas in France.[49] In early 1798, he suggested the establishment of a police force against the ‘strong advance of the revolutionary spirit’[50] and proposed a secret police for bigger cities.[51] These ideas had already been brought up during the reign of Joseph II but were too fiercely opposed by the nobility.[50] While a secret police was established to monitor the mood in ten cities, there is no proof of the Palatine ever collaborating with them.[51]

Effect of first two visits to Russia[edit]

A major turning point in Archduke Joseph's attitude towards his office were his travels to the Russian Empire. In 1798 and 1799, he visited Saint Petersburg twice to finalise marriage plans with Emperor Paul I's daughter. During the negotiations, he suffered humiliations because of diplomatic mistakes by the Viennese court, which led to him to view his brother's administration with a critical eye. Prior to 1798, he served to execute imperial will in Hungary, and during his short first marriage, he worked little. After the loss of his wife, when his focus returned to public matters, he approached them with an opinion of his own.[52]

On 9 June 1801, he wrote a referral to his brother asking him to release the remaining political prisoners of the Martinovics uprising, including author and language reformer Ferenc Kazinczy. He urged the Emperor to gather a diet, allow a reform of public education, establish a second university, and take measures to boost trade. He was concerned with what a ‘relatively sparse population’ the ‘vast, abundant area’ of Hungary supported (different estimations give between 8.1 and 9 million inhabitants[53][54][55][56] for an area of 282,870 km2/109,220 sq mi[57] in 1790) and at what a ‘backwards stage of culture, among what primitive economic conditions’ these people lived.[58]

The report of 1801[edit]

On 17 June 1801, Joseph submitted a report to Emperor-King Francis, explaining his view and opinions on Hungary. He characterised public opinion and morale as high, except for a few ‘atheistic and freethinking’ young people.[59] While he was mostly satisfied with the work of priests, he would have preferred to have less parishes but all of them with good pastors.[60] He criticised members of the aristocracy for not striving for knowledge and ‘useful occupations’, that few of them ran for public office and most of those who did neglected their positions.[61] He proposed that in the future, only those should be promoted to the coveted rank of chamberlain or court councillor who had proved themselves in public service.[62] Joseph also emphasised the potential of the lower nobility, advising the court to show more appreciation towards them.[62] In detailing his view on all classes of Hungarian society, he was the most dissatisfied with the bureaucracy, faulting them for a lack of ‘zeal’ and ‘diligence’ and for not keeping classified information secret.[63] His proposed solutions focused not on oppressing opposition but on maintaining the country's good spirits, for example by permitting diets.[63]

The diet of 1802[edit]

Background[edit]

During the French Revolutionary Wars, Archduke Charles, Joseph's brother and leader of the Imperial Army, planned a major reform of military training and service, and demanded recruits and money from Hungary.[64] This could only be granted by the diet, and the Viennese court was afraid that the nobility would bring up their many complaints if one was gathered.[65] Joseph worked to convince his brother otherwise, presenting his arguments in his report of June 1801. Two days later, on 19 June, he asked Francis to declare the time and place of the diet, proposing March 1802 and Buda. He also suggested that the sovereign resolve some of the grievances the Hungarian nobility ahead of the diet, such as re-attaching Dalmatia to Hungary, or allowing a free export of grain (which had been forbidden to keep the enemy French from acquiring it) to boost the economy.[66] The pressing situation of the Imperial Army in the ongoing war finally led to the Viennese court accepting that the diet needed to be consulted,[67] but in May and in Pozsony.[68]

Despite tragedies in his personal life (the death of his infant daughter and his wife in early 1801), as well health concerns, the Palatine prepared thoroughly for the assembly, struggling with the reluctance of the Emperor and his ministers who were unwilling to compromise.[68] They denied to help the Hungarian economy in any way and did not want to consider re-attaching Dalmatia. They also refused to consider any educational reforms, arguing that this matter was to be decided by the monarch alone, without having to consulting the nobility.[69] The Viennese legislature thought that Hungary did not contribute proportionally to the Habsburg monarchy, while many Hungarians criticised the government for suppressing opportunities for industrial development.[70]

The diet[edit]

After a preliminary session on 6 May, the Diet of 1802 was opened on the 13th, with multiple members of the Habsburg dynasty present.[71] In his opening speech, Joseph aligned himself more with Hungarians than with his own family, promising to protect the country's rights if the Emperor-King tried to infringe upon them,[58] but emphasised the importance of ‘complete trust’ in the sovereign.[71]

The Emperor is my brother; but if he should violate the least of your rights, I would forget the ties of blood to remind myself that I am your palatine.

— Archuke Joseph, opening speech of the 1802 diet

The main goals of the deputies was to pass legislation to support the agricultural and industrial development of Hungary, stifled by the customs regulations of Maria Theresa and Joseph II. Cities, towns, and guilds compiled proof and wrote explanations of why the existing system was unjust and unsustainable, asking for an equal treatment of all parts of the Habsburg monarchy in economic regulations. Deputies were selected to present this material, including Baron József Podmaniczky, a member of the governing council and Miklós Skerlecz, főispán of Zagreb County.[72]

Skerlecz argued that the main goal of Austrian customs regulations was to prevent the founding of factories in Hungary and to exclude Hungarian merchants from international trade.[72] Another economist supporting a major reform was Gergely Berzeviczy. He wrote a detailed thesis endorsing the deputies' recommendations, including rebuttals against accusations by the Viennese government who claimed that it was the ‘laziness’ and ‘primitiveness’ of Hungarians that made the country less useful than it could have been to the Habsburg monarchy.[73] In summary, the Hungarians wanted a more independent economy, free from the ‘shackles’ put in place by previous sovereigns.[74] Despite their efforts, Austrians were dismissive,[75] and Emperor-King Francis committed to the old regulations.[76]

Another problem raised at the diet was that of banknotes, which had been used since 1762.[76] The acceptance of banknotes as payment was made compulsory in 1800. As a result of government debt, inflation was concerning.[77] Already before the diet, the Palatine had alerted the King that the Hungarian nobles would bring up these issues.[78] Given how serious the monarchy's troubles were and how distrustful the Viennese government and the Hungarian nobility were of each other, the diet promised to be difficult. One possibility was that the more radical Hungarian proposals would cause the Austrian party to become antagonistic and defensive, strengthening their reactionary and absolutist factions. This would have made necessary reforms impossible.[79]

Despite these signs of probable failure, the Palatine worked hard, studying previous negotiations between the two parties. When he learned that the főispáns of each county were commanded to submit the instructions given to their respective envoys to the Austrian chancellery, he was concerned that this would cause distrust among Hungarians. He gave frequent descriptions of public sentiment to the Emperor-King, telling him that while most people deemed the royal demands just and necessary, opinions differed on methods of execution.[80] To elevate spirits, some members of the imperial family moved to Pozsony for the time of the assembly, and various feasts and religious ceremonies were held.[71]

As a result of private meetings, the sentiments of envoys with more extreme opinions were consolidated by the time of the diet, and initial negotiations seemed to be promising.[71] However, the royal propositions of 13 May did not mention any of the subjects that concerned the Hungarians but asked for new recruits and higher taxes.[81] On the 21st, the nobles asked for time to discuss the demands and for economic reforms to ease the introduction of higher taxes.[82] Emperor-King Francis received their referral well,[83] and it seemed that the efforts of Archduke Joseph would result in a smoother process.[84] However, conservative and anti-constitutional circles in Vienna raised concerns about the assembly debating the Emperor-King's proposals in any way, and while negotiations were peaceful and well-intentioned, both parties remained unwilling to compromise.[84] During the following talks, Joseph played the role of mediator and calmed the Hungarians,[85] who worried that the Viennese court wanted to introduce continuous recruitment to render diets unnecessary.[86]

Tensions were increased by a formal royal letter on 12 July, which emphasised royal prerogatives on the counsel of Archduke Charles. From this, the envoys deduced that the King did not want to respect their right to grant new taxes and recruits. On 18 July, a report to Archduke Charles characterised the mood of participants as ‘confused’ and ‘withdrawn’.[86] To avoid further escalation, Joseph talked to Francis personally in early August. He described how determined the envoys were to achieve their goals and that they represented the general opinion of Hungary; he openly told the King that if Vienna insisted on the content of the letter of 12 July, the situation would deteriorate beyond help.[87] He expressed his support for some of the economic concerns of the assembly.[88] As a result, a new royal letter on 14 August focused more on achieving consensus and stated that all decisions would only be in effect until the next diet.[89] In a separate, confidential letter, the sovereign entrusted the Palatine with settling matters ‘favourably for the state’, giving guidelines.[90]

By this time, however, participating nobles had become distrustful of the King and insisted on all of their demands, despite Joseph trying to convince them to compromise.[91] He told the envoys that if they did not accept his mediation, he would advise the Emperor to refuse all of their requests. In response, the diet voted to allow for twelve thousand new recruits and promised to find a solution for continuous recruitment on the next diet.[92] The Diet of 1804 did not deliver on these promises.[58]

Joseph had grown tired of the assembly by mid-August, and he asked the Emperor-King to settle some minor issues and close the diet.[93] Economic reforms were never seriously considered, especially because the issue was brought up on 14 July, the same day the ill-received royal letter of the 12nd was presented to the envoys.[94] After more peaceful negotiations during September, the Emperor-King's hesitance to re-attach Modruš-Rijeka County meant that the diet ended in distrust and pessimism in October.[95] To the Palatine, King Francis wrote that Hungarian nobles ‘only want gains for themselves, without looking to the good of the whole’ empire, and that he would need ‘great resignation’ to forget their ‘behaviour against [him]’.[96]

The reckless eagerness to achieve Your Majesty's intentions right now, which has not given me time to think about its possibility and feasibility, insufficient deliberation, [and] [...] the thought that I might, with my authority and the trust of the estates placed in me, see through a matter which had repeatedly failed before—which flattered my self-esteem—tempted me to make a proposal to Your Majesty without having considered the consequences. This, however, would have been far from drawing the present consequences had not the false arguments and harsh expressions [...] in said resolution excited tempers. [...] [T]he stubborn discussions with the estates prior to the assembly had upset me [...] and at the conference [...] I—to my shame—therefore paid attention to the words rather than to the substance and thus completely spoiled the matter. Your Majesty cannot believe [...] how I feel when I consider what more could have been accomplished by this parliament, and how little more will be possible to be accomplished by it.

— Archduke Joseph in a letter to his brother, Emperor-King Francis on 25 August 1802, quotes Domanovszky

Third journey to Russia[edit]

Since Archduke Joseph had developed a close relationship with the House of Romanov and especially his former mother-in-law Empress Dowager Maria Feodorovna, his brother relied on his help in keeping the Russians allied during the Napoleonic Wars.[97] In December 1802, the Empress Dowager invited Joseph to Saint Petersburg. He arrived on 30 March,[98] and found the imperial court in three factions around the Emperor Alexander I, Empress Consort Elizabeth Alexeievna, and the Dowager Empress.[99] Joseph joined the Dowager's circles.[100] While he tried to seem neutral, his inclinations soon became public knowledge.[101]

During his stay, he ate lunch with the Emperor almost every day and spent the afternoons with him.[101] Alexander disclosed his opinions and worries, which Joseph reported to Vienna. Still, he enjoyed the company of the Empress Dowager and Grand Duchesses Maria and Catherine Pavlovna more, spending evenings with them.[102] Joseph's preference for the Dowager's faction displeased the Russian court, particularly when he declined a tour of the country with the Emperor. The imperial couple found the fact that he ignored the Empress Consort's sister, Princess Amalia of Baden offensive, as they wished him to marry her.[103] When it became obvious that he was not interested in the Princess, it seemed unclear why he had even travelled to Saint Petersburg.[103] Sensing these tensions, the Archduke's Hofmeister János Szapáry urged him to return to Buda and asked Emperor Francis to order him back under some pretense. Joseph refused to consider leaving.[104] Eventually, after the imperial family tried to pressure him into marrying Princess Amalia, he decided to leave in June,[105] and spent his last few weeks in Pavlovsk as the Empress Dowager's personal guest.[106] Once he had returned to Vienna, he honestly described the foreign opinion on the Habsburg monarchy to Emperor Francis and urged him to be more pro-active in his governance.[58]

Other achievements[edit]

During the decades of his palatinate, Archduke Joseph continued to mediate between his dynasty and the Hungarian people. He tried to moderate and unify the latter, especially at the Diet of 1832–1836. Then, he persuaded the House of Magnates to not veto the proposals of the House of Representatives. In 1840, he obtained imperial amnesty for the Hungarian progressives László Lovassy, Lajos Kossuth, and Miklós Wesselényi. When, in 1843, the Viennese government tried to shut down the Védegylet, an association helping Hungarian industries by promoting and purchasing their products, it was the Palatine who protected it.[2]

Hungarian education[edit]

In 1802, Joseph supported the establishment of a national library, which would later develop into the National Széchényi Library and the Hungarian National Museum. He contributed valuable codices and books to its collection. In 1826, he founded the National Royal Joseph Institute and School of the Blind (today the National Institute for the Blind). In 1835, he participated in founding of The Royal Hungarian Ludovica Defense Academy (today Zrínyi Miklós National Defence University) to provide training for cadets.

At the Diet of 1825, which was gathered after a break of thirteen years on Joseph's insistence, the Hungarian Academy of Sciences was established, to which he contributed ten thousand forints. In 1846, he founded the Royal Joseph Polytechnic (today's Budapest University of Technology and Economics).[2]

Transportation and economy[edit]

For the development of Hungarian transportation, he founded the Kőbánya horsecar line in 1827–28 and the first train line of the country between Pest and Vác. On this, he collaborated with Count István Széchenyi. He helped to establish the Hungarian Commerce Bank of Pest, and ran a demonstration farm on his Alcsút estate, introducing new methods and species to Hungary.[2]

Remodelling of Pest[edit]

The first mention of Archduke Joseph's plans to elevate Pest, a neglected town, into a modern European city is from 16 November 1804, when he wrote to city leadership that the sovereign himself wanted Pest to be regulated and improved, although there is no proof of the King being interested. Joseph appointed Hungarian-German architect József Hild to oversee the works, and in October 1808, the Pesti Szépítő Bizottság, 'Beautifying Committee of Pest', headed by the Palatine himself, was established.[58] He proposed and oversaw the construction of Lipótváros and the City Park, which he supplied with trees from his private park in Alcsút. In 1815, he supported the building of Buda Observatory on Gellért Hill. He bought Margaret Island and turned it into a park. When the 1838 flood devastated Pest-Buda, he personally directed the rescue mission and did helped relieve those affected.[2]

Personal life[edit]

First marriage[edit]

Background[edit]

In 1798, Joseph learned from Emperor-King Francis that he needed to marry a member of the Russian imperial family in order to secure Emperor Paul I as an ally in the French Revolutionary Wars.[107] The proposed bride was fifteen-year-old Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna, Paul's eldest daughter. There had been talks that she might marry Archduke Charles instead, but there was a bigger age difference between them, and Francis thought that Joseph was better suited for the match. The Russian court also preferred him.[108] In January 1799, Joseph left for Saint Petersburg[109] travelling under the pseudonym of ‘Count Burgau’,[110] and arrived on 20 February (O.S.). He was warmly welcomed and hugged by the Emperor and then presented to the Empress and the grand duchesses.[109] The Archduke was enchanted by the ‘charm’ and ‘reserved modesty’ of Alexandra Pavlovna, a tall, blonde girl,[111] whom he described as ‘well-built and very beautiful’, as well as ‘clever’ and ‘talented’.[110] In a letter to his brother Francis, he declared their meeting the ‘happiest moment of [his] life’ and Alexandra a ‘noble princess with whom [he] would be happy’.[41]

I cannot thank Your Majesty's graciousness enough that it has appointed her for me as partner in life and I am convinced that with this marriage my domestic bliss is assured for the entirety of my life.

— Archduke Joseph to Emperor-King Francis about his bride, quotes Hankó and Kiszely in 'A nádori kripta'

Alexandra Pavlovna's mother was Empress Maria Feodorovna, but until the age of thirteen, her education had been supervised by her grandmother Catherine the Great.[112] She received instruction in French, German, music, and drawing with her younger sister Elena Pavlovna, with whom she was very close. She was a diligent student and talented in the arts. She had been intended to marry King Gustav IV Adolf of Sweden who did not go to their engagement where then-thirteen-year-old Alexandra Pavlovna was waiting in a bridal dress. The Russians insisted that the future queen be allowed to keep her Orthodox religion, which the Swedish refused to accept, and the engagement came to nothing.[113]

Joseph asked for Alexandra Pavlovna's hand in marriage from her parents on 22 February (O.S.) in her presence, and they gave their blessing. On the betrothal ceremony, the bride wore díszmagyar and the engagement rings were exchanged by the Emperor himself. He spent another month in Saint Petersburg and left on 20 March[110] to assume a role of military leadership. A faction headed by Baron Johann Amadeus von Thugut conspired to replace Archduke Charles with Joseph, which he himself did not support.[114] These plans came to nothing as Emperor-King Francis was too indecisive to enter an open conflict with his popular brother.[115] Thaz Joseph was not appointed nullified his reason for leaving Russia so soon and evoked the distrust of Emperor Paul, who would have liked to have seen his future son-in-law lead the Imperial Army.[116]

Joseph returnd to Buda on 13 May and started to prepare for his wife's arrival, re-decorating the apartments of Buda Castle and gathering female courtiers.[110] He urged his brother the Emperor to designate a day for the wedding, but Francis did not answer his letters until 19 August.[117] Emperor Paul grew disillusioned with the alliance, so Joseph was sent back to Russia to sway him, and the wedding date was finally announced as 30 October.[117]

Arriving on 15 October in the Gatchina Palace, he was initially welcomed warmly, but after news of lost battles, the Emperor refused to talk to him.[118] The Viennese court complicated the situation by demanding that the Roman Catholic wedding precede the Orthodox one, and be celebrated by the Archbishop of Lemberg (today Lviv, Ukraine) who was not yet in Russia. The Emperor was angered by the idea of postponing the ceremony, and everyone was relieved when the Archbishop arrived on 26 October. The Austrians then had to accept that the Orthodox ceremony would be first.[119] On the 29th, Joseph visited the Emperor without announcement, asking for his blessing and committing himself to solving their diplomatic issues ‘openly’ and ‘honestly’.[120] This made a great impression on Paul and the wedding could proceed according to plans.[121]

Marriage[edit]

On 30 October, after Emperor Paul had awarded Joseph the Order of St. Andrew, he could finally marry Alexandra Pavlovna.[121][122] The wedding was first celebrated according to Orthodox rites in the imperial chapel of Gatchina Palace, then the Roman Catholic ceremony was held.[122] The following days were overshadowed by news of lost battles and subsequent tension between Austria and Russia,[123] as well as disagreements over the specifics of the dowry and the dower.[110] The Emperor again refused to see his son-in-law, but reconciled with him shortly before the young couple's departure on 2 December, which was very emotional.[124] After a visit to Vienna, they arrived in Buda on 11 February.[125] The Austro-Russian alliance soon fell apart as Emperor Paul pulled out.[126]

During their short marriage, the couple lived happily.[125] There were many festivities thrown for and by the new archduchess, including concerts, balls, hunts, and a harvest festival on Margaret Island, to which she usually wore Hungarian-style dresses. The couple rode and walked around Buda, once finding the village of Üröm, which Alexandra liked so much that Joseph bought it for her, planning to build a summer residence there.[110][122] Towards the end of her pregnancy, Alexandra often visited Üröm.[110] She enjoyed Hungarian folk music and talked to delegations of tóts (old name for Roman Catholic South Slavs living in Hungary) in a mix of Russian and Slovak.[110] For Joseph's birthday in 1800, she commissioned Haydn to conduct his oratorio The Creation and also invited Beethoven to perform in Budapest.[128]

As a result of her kindness and consideration, Alexandra became so well-liked by Hungarians that they started to call her magyar királyné ('Hungarian queen consort'), the dismay of the Viennese court and especially Empress Maria Theresa (who was, in fact, queen consort of Hungary). Whenever the palatinal couple visited Vienna, Alexandra was humiliated in small ways, and they were not accommodated in the palace with the rest of the imperial family but in a remote garden house.[110]

Pregnancy, birth of daughter, and death[edit]

Alexandra soon became pregnant. While the first stages were easy,[110] she developed a fever two days before giving birth.[129] On 8 March 1801, early in the morning, a daughter was born after prolonged labour, but she was reportedly ‘very weak’ and died within the day,[129] possibly the hour.[110][130] According to Joseph's biographer Domanovszky, the child was called Alexandra,[129] but Hankó and Kiszely, who exhumed and examined the body of the infant, state that she was registered as Paulina in her death certificate. She had no separate entry in the baptism registry of the Capuchin Church of Buda, suggesting that she was christened after her death. Her casket was inscribed with the same name. She was buried in the Capuchin church in the presence of Hungarian dignitaries.[110] In 1838, she was transferred to the Palatinal Crypt with urns containing the intestines and heart of her mother. An investigation in 1978 determined that the remains were those of a fully and normally developed newborn, not at all ‘very weak’, and concluded that she probably died of hypoxia during the long delivery.[110]

The death of the baby devastated both parents, but at first it seemed like the mother would recover. Despite being treated by four doctors, her condition did not improve, and the breast milk she could not nurse with worsened her fever. From 12 March, she was treated against typhoid fever,[110] and early on the 15th, she became delirious, dying on 16 March.[129] Emperor-King Francis ordered a courtly mourning period of six weeks, with some modifications because of the late Archduchess' religion.[110]

The embalmed body was laid on an ornate catafalque in the Russian Orthodox chapel built for Alexandra's personal use. It lay in state for three days before being placed in a separate building in the garden for six weeks, as Orthodox customs commanded. Alexandra was buried on 12 May at noon in the Capuchin Church, her clothes were remade for clerical usage and Joseph gifted her mineral collection the Royal University of Pest eight years later.[110]

On 17 March, Joseph went to Vienna, then travelled around Italy. When he returned in the spring of 1802, he started the construction of the Saint Alexandra Chapel in Üröm, where Alexandra had requested to rest. She was reburied there in 1803,[110] and, after multiple exhumations and disturbances, is there as of 2024.[131] After a grave robbery in the late 1980s, an investigation was carried out, determining that Alexandra Pavlovna suffered and probably died of tuberculosis. The examinations ruled out the possibility of poisoning, rumours of which had surfaced in the years following her death.[110]

Marriage plans after Alexandra Pavlovna's death[edit]

In early 1803, Archduke Joseph visited his late wife's family on his mother-in-law's invitation.[98] Part of the reason for the invitation was to arrange a new marriage for him: Empress Elizabeth Alexeievna wanted him to wed her older sister, Princess Amalia of Baden,[98] a plan supported by the new emperor, Alexander I.[101] Amalia was known for her kindness and goodness but not her beauty, and Joseph was not attracted to her, deciding early on that he would not propose. For her part, the Princess did not like Joseph's personality.[98] Empress Elizabeth persuaded Empress Dowager Maria to try to convince the Archduke to marry Amalia, as she had great influence over him. Joseph did not want to offend his mother-in-law, and waited for weeks before rejecting the idea.[132]

During his stay, he grew attached to his fifteen-year-old sister-in-law, Grand Duchess Catherine Pavlovna, who had been promised in marriage to Electoral Prince Ludwig of Bavaria.[100] However, he knew how strict the Orthodox church was regarding incest laws prohibiting marriage between siblings-in-law, and thus did not formally propose.[101]

Some time later, the Palatine considered marrying Princess Charlotte of Saxe-Hildburghausen, daughter of Frederick, Duke of Saxe-Hildburghausen after her engagement to Grand Duke Konstantin Pavlovich of Russia had been broken off, but there is no information on why this plan never materialised. In November 1803, there were signs that the Emperor might agree to the marriage between his sister Catherine and the Palatine, who asked Empress Dowager Maria and received a final negative answer. In 1804, he attempted to find a bride from Bavaria, but decided not to risk proposing because of French disapproval.[133]

The Archduke saw Grand Duchess Catherine Pavlovna two more times: first, in 1809, when she travelled through Hungary on her way to marry Duke George of Oldenburg, the Palatine escorted her through the country. In 1815, by when Catherine Pavlovna herself had also been widowed, they met at the Congress of Vienna. Contemporary rumour suspected that the two would revisit their old marriage plans, but there were no signs of this happening. Archduke Joseph married someone else that year, and Catherine married King William I of Württemberg and died in 1819.[134]

Second marriage[edit]

After fourteen years of widowhood, with the Napoleonic Wars over, Joseph decided to remarry in 1815.[58] On 30 August 1815, in Schaumburg Castle, he married Princess Hermine of Anhalt-Bernburg-Schaumburg-Hoym, the seventeen-year-old eldest daughter of the late Victor II, Prince of Anhalt-Bernburg-Schaumburg-Hoym and Princess Amelia of Nassau-Weilburg.[58] The bride, twenty-two years younger than the groom, was from a small German state and practiced Calvinism. She became an active and well-liked nádorné ('wife of the palatine'), especially popular among Protestants.[58] In 1817, she founded the first charitable women's association (‘nőegyesület’) in Hungary.[135] On 14 September 1817, she prematurely gave birth to twins, Hermine and Stephen. The labour was complicated, and Hermine died of postpartum infections within twenty-four hours.[58]

Joseph was not present for the birth as it was only expected to occur October, and he had gone to welcome his mother-in-law to Hungary. After lying in state for two days, Hermine was buried in the crypt of the Calvinist church on Széna tér (today Kálvin tér) which she had helped build with a donation in 1816. The 1838 flood damaged the crypt and carried away the urns containing her heart and intestines but left the casket intact. Afterwards, Joseph obtained an ecclesiastical license to transfer Hermine's remains to the Palatinal Crypt despite her not being a Catholic. She was placed in a separate chamber within the crypt[58] and still rests there as of 2023,[136] now in a more central place.[58]

Third marriage[edit]

After two short, tragic marriages and in a difficult economic and political climate, Archduke Joseph wanted to marry for a third time. Looking for a companion in his everyday problems,[58] he chose twenty-two-year-old Duchess Maria Dorothea of Württemberg, daughter of Duke Louis of Württemberg and Princess Henriette of Nassau-Weilburg.[58] The Kingdom of Württemberg had been an ally of the Austrian Empire at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, which was probably why Emperor-King Francis supported the match. The couple with an age difference of twenty-one years married in the castle of Kirchheim unter Teck on 24 August 1819.[58]

Maria Dorothea spent her life as nádorné with charitable work, especially supporting the Lutheran church in Hungary to which she belonged, besides teachers and schools. She founded and supported many charitable societies and institutions[58][137] and helped Joseph in his job as palatine. Their main shared cause was making Hungarian the country's official language (instead of Latin). On New Year's Day 1826, she gave a speech in Hungarian, the first time a Habsburg archduchess addressed the country in its own language. Maria Dorothea actively participated in the social life of Pest, frequenting the houses of the Károlyis and the Széchenyis, with whom she conversed in Hungarian. On many occasions, she wore a Hungarian-style dress.[58]

Family life[edit]

The couple's first child, Elizabeth Caroline Henrika was born on 30 July 1820, and died twenty-three days later on 23 August. She was the first person to be buried in the Palatinal Crypt, without embalming or much ceremony. According to her death certificate, she died of ‘internal hydrocephalus’ (‘inneren Wasserkopfe’), and a later investigation found signs supporting this claim, besides determining that she had been born prematurely.[58] Their next child, Alexander Leopold Ferdinand was born on 6 June 1825. He was described as kind, clever, and being in great health. In November 1837, aged twelve, he started to suffer from diarrhea and developed ymptoms of scarlet fever. It is unclear what caused his death; it could be complications of scarlet fever or, more likely, a mysterious infectious disease appearing at times during the century which consisted of recurrent fever, jaundice, and strong sweating. Hepatitis, paratyphoid fever, and typhoid fever have also been suggested. The child was buried silently in the Palatinal Crypt.[58]

The three youngest children, Elisabeth, Joseph Karl, and Marie Henriette survived to adulthood.[58] Maria Dorothea also raised her two step-children, and Joseph adored the older twin, Hermine, a favourite of Hungarian high society. She died unexpectedly in 1842, aged twenty-five, devastating her father, and was widely mourned.[58]

After Joseph's death in 1847, Maria Dorothea lived for the rest of her life in Alcsút Palace and did not play a significant role in culture or politics. She died after an illness on 30 March 1855, at the age of fifty-eight, and was buried in the Palatinal Crypt on 4 April.[58]

Death and legacy[edit]

In September 1845, the Archduke celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of his appointment to Hungary, and the next year marked the same for his palatinate. By then, he was in ill health and became bedridden in early October 1846. The press reported on his recovery, and he was well for a short time. He felt the need to secure the governorship for his elder son Stephen upon his death. On 11 January 1847, he took extreme unction and received Stephen, who brought news of his sister Elisabeth's engagement, which delighted their father. Then, they conversed about the state of their family and Hungary, with the Palatine giving advice to his son and successor. In the end, he exclaimed that he would want to achieve a few more things in Hungary, commanding Stephen do to ‘what [his] hands can no longer do’.[58]

On 12 January, he asked to be taken to the window to look at Pest, by now a capital city with a hundred thousand inhabitants. His doctors reported on his health three times a day to the public, writing of an ‘incessant decline of vitality and the accumulation of calamitous symptoms’, which did not ‘allow any comforting report to be made’. Kept awake by constant hiccups, he slept little and his speech was difficult to understand. On 13 January at dawn, he blessed his children before dying at nine in the morning, aged seventy-one.[58]

Following an autopsy, the late Archduke's body was embalmed, and he lay in state until his burial on 18 January. He was interred in the Palatinal Crypt wearing díszmagyar, and the cause of his death was given as paralysis intestinorum, intestinal paralysis. After grave robbers had disturbed the body, a medical investigation determined that he indeed died of paralysis and a consequent circulatory shock, but the specific diagnosis remains unknown. One proposed disorder which could lead to the symptoms he displayed was prostate enlargement.[58]

Archduke Joseph's son Stephen was elected the next (and last) nádor, while Joseph was honoured as one who had been ‘born a Habsburg but died a Hungarian’. Many eulogised him, among them his then-ruling nephew Emperor-King Ferdinand I/V, who called him a ‘most valued advisor who had always guarded the constitution of Hungary with vigilant care’, and Lajos Kossuth, who depicted him as a patriarch whom all parties and factions respected. The first law of 1847–48 enshrined his memory as that of one who had ‘deserved the gratitude of the nation entirely’ with his ‘untiring zeal’ in guiding the affairs of Hungary for half a century under difficult circumstances. On 25 April 1869, his statue by Johann Halbig was unveiled in the presence of the then-ruling imperial and royal couple, Franz Joseph I and Elisabeth, a demonstration of their trust and love of Hungary following the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867.[58]

Issue[edit]

Archduke Joseph had eight children from three marriages, five daughters and three sons. Two daughters died in infancy and a further one in childhood. His three surviving children from her last marriage married and had issue, Archduke Joseph Karl continuing the Hungarian or Palatinal branch of the House of Habsburg-Lorraine, which had been founded by his father. His older son Stephen became the last palatine of Hungary, his term cut short after less than a year by the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. One of his daughters, Marie Henriette became queen consort of the Belgians and the mother of Crown Princess Stéphanie of Austria.

His children were:

- by Grand Duchess Alexandra Pavlovna of Russia (born 1783, married 1799, died 1801):

- Archduchess Alexandrina Paulina of Austria (8 March 1801, Buda, Kingdom of Hungary);[110]

- by Princess Hermine of Anhalt-Bernburg-Schaumburg-Hoym (born 1797, married 1815, died 1817):

- Archduchess Hermine Amalie Marie of Austria (14 September 1817, Buda – 13 February 1842, Vienna, Austrian Empire), princess-abbess of the Theresian Institution of Noble Ladies between 1835 and 1842, never married and had no issue;

- Archduke Stephen Francis Victor of Austria (14 September 1817, Buda – 19 February 1867, Menton, France), palatine of Hungary between 1847 and 1848, never married and had no issue;[58]

- by Duchess Maria Dorothea Louisa Wilhelmina Carolina of Württemberg (born 1797, married 1819, widowed 1847, died 1855):

- Archduchess Elizabeth Caroline Henrika of Austria (30 July 1820, Buda – 23 August 1820, Buda), died in infancy;

- Archduke Alexander Leopold Ferdinand of Austria (6 June 1825, Buda – 12 November 1837, Buda), died in childhood;

- Archduchess Elisabeth Franziska Maria of Austria (17 January 1831, Buda – 14 February 1903, Vienna) married first her second cousin Archduke Ferdinand Karl Viktor of Austria-Este in 1847 and had issue and second her first cousin Archduke Karl Ferdinand of Austria in 1854 and had issue;

- Archduke Joseph Karl Ludwig of Austria (2 March 1833, Pozsony – 13 June 1905, Fiume, Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia) major general in the Austro-Hungarian Army, married Princess Clotilde of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in 1864 and had issue;

- Archduchess Marie Henriette Anne of Austria (23 August 1836, Buda – 19 September 1902, Spa, Belgium), queen consort of the Belgians as the wife of King Leopold II, married in 1853 and had issue, including Crown Princess Stéphanie of Austria;[58]

- By an unknown woman:

- Gavio Clùtos (2 March 1810 – January 1859).[citation needed]

Honours[edit]

Empire of Brazil: Grand Cross of the Southern Cross[138]

Empire of Brazil: Grand Cross of the Southern Cross[138] Habsburg Monarchy:

Habsburg Monarchy:

- Knight of the Golden Fleece (1790)[139]

- Grand Cross of St. Stephen, in Diamonds (1794)[140]

- Gold Civil Cross of Honour (1813/14)[138]

Kingdom of Prussia

Kingdom of Prussia

- Knight of the Black Eagle, 14 August 1844[141]

- Knight of the Red Eagle, 1st Class[138]

Russian Empire

Russian Empire

Ancestry[edit]

| Ancestors of Archduke Joseph of Austria (Palatine of Hungary)[142] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References[edit]

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, pp. 99–100.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "230 éve született József nádor" [Palatine Joseph was born 230 ago]. Múlt-kor történelmi magazin (in Hungarian). 9 March 2006. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 101.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 101–102.

- ^ a b c Domanovszky 1944, p. 102.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 102–103.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, pp. 103–104.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 109.

- ^ a b c d D. Schedel 1847, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Hankó, Ildikó; Kiszely, István (1990). "József, a nádor" [Joseph, the Palatine]. A nádori kripta [The Palatinal Crypt] (in Hungarian). Babits Kiadó. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2022 – via Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 107.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 107–109.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, pp. 110–111.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 111.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 112–113.

- ^ a b c d Nagy-Luttenberger, István (11 July 2020). "1795. július 12. – Sándor Lipót nádor halála". Magyarságkutató Intézet. Retrieved 7 July 2022.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 113.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 114.

- ^ a b c d D. Schedel 1847, p. 8.

- ^ Lestyán 1943, p. 25.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 184.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 184–185.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 185.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 187.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 197.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 198.

- ^ a b c d Domanovszky 1944, p. 200.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 201.

- ^ a b c Domanovszky 1944, p. 202.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 203.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 204.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 203–204.

- ^ a b c Domanovszky 1944, p. 205.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 206–208.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 212.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 209.

- ^ D. Schedel 1847, p. 9.

- ^ a b Lestyán 1943, p. 26.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 216–217.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 270–272.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 273.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 274.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 275.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 276–277.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 279.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 281.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 282.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 283.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 256, 288.

- ^ Patai, Raphael (1996). "The Jews Under Maria Theresa (1740–80)". The Jews of Hungary. History, Culture, Psychology. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-8143-2561-2. Retrieved 15 July 2022.

- ^ Halász, Zoltán (1978). Hungary. A Guide with a Difference. Corvina Press. pp. 20–22. ISBN 978-9631330076. LCCN 79317902.

- ^ Bush, M. L. (2000). Servitude in Modern Times. Wiley. ISBN 978-0745617305. LCCN 00035645.

- ^ Andorka, Rudolf (1995). "Household Systems and the Lives of the Old in Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Hungary". In Kertzer, David I.; Laslett, Peter (eds.). Aging in the Past. Demography, Society, and Old Age. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520084659. LCCN 93033288.

- ^ Tóth, Pál Péter; Valkovics, Emil (1996). Demography of Contemporary Hungarian Society. Boulder: Social Science Monogrqphs. p. 15. ISBN 978-0880333580. LCCN 96061475. OCLC 36475773.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Hankó, Ildikó; Kiszely, István (1990). "A nádor, aki Habsburgnak született és magyarnak halt meg (József nádor további élete)" [The Palatine Who was Born a Habsburg and Died a Hungarian (The Later Life of Palatine Joseph)]. A nádori kripta [The Palatinal Crypt] (in Hungarian). Babits Kiadó. Retrieved 8 July 2022 – via Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 293.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 294.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 294–295.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 295.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 296.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 303–304.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 304.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 305.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 305–306.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 310.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 311–313.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 313–314.

- ^ a b c d Domanovszky 1944, p. 346.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 323.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 332–333.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 333–334.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 338.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 339.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 342–343.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 343.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 344.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 345.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 346–347.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 347.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 348.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 349.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 352.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 355.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 356.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 357–358.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 359–360.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 360.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 360–361.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 361.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 362.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 363.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 365.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 256–257.

- ^ a b c d Domanovszky 1944, pp. 257–258.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 259.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 260.

- ^ a b c d Domanovszky 1944, p. 261.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 261–262.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 262.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 263–264.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 266.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 265.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 225–227.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 230–231.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 231.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Hankó, Ildikó; Kiszely, István (1990). "Alexandra Pavlovna". József, a nádor [The Palatinal Crypt] (in Hungarian). Babits Kiadó. Archived from the original on 8 February 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2022 – via Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 232.

- ^ Massie 1990, p. 36.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 232–234.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 237.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 239.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 240.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 241.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 247.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 247–249.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 249–250.

- ^ a b c Domanovszky 1944, p. 250.

- ^ a b c d Lestyán 1943, p. 28.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 250–252.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 252–253.

- ^ a b Domanovszky 1944, p. 253.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 253–255.

- ^ Lestyán 1943, p. 29.

- ^ Lestyán 1943, p. 31.

- ^ a b c d Domanovszky 1944, p. 255.

- ^ Lestyán 1943, p. 32.

- ^ Maklári, István (10 January 2013). "Szent Alexandra sírkápolna – Üröm | Magyar Ortodox Egyházmegye". Orthodoxia. Retrieved 10 June 2024.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 265–267.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, p. 267.

- ^ Domanovszky 1944, pp. 267–268.

- ^ Pillera; Simor (1897). A Pallas nagy lexikona. Az összes ismeretek enciklopédiája [The Great Lexicon of Pallas. An Encyclopedy of All Knowledge] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Pallas Irodalmi és Nyomdai Részvénytársaság. Archived from the original on 4 May 2007. Retrieved 8 July 2022 – via Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár.

- ^ "A Múzeumról" [About the Museum]. Magyar Nemzeti Galéria (in Hungarian). A Habsburg nádori kripta. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ Cserháti, Endre. "Semmelweis Egyetem I. sz. Gyermekklinika, alapítva 1839-ben Szegény-gyermekkórház Pesten névvel" [Semmelweis University No. 1 Child Clinic, Founded in 1839 with the Name Poor-child Hospital in Pest]. SOTE Múzeumok. Archived from the original on 27 December 2011. Retrieved 8 July 2022.

- ^ a b c "Genealogisches Verzeichnis des gefammten Hauses Oesterreich", Hof- und Staatshandbuch des österreichischen Kaiserthumes, 1860, p. 6, retrieved 23 July 2020

- ^ "Ritter-orden", Hof- und Staatshandbuch des österreichischen Kaiserthumes, 1847, p. 7, retrieved 23 July 2020

- ^ "A Szent István Rend tagjai" Archived 22 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Liste der Ritter des Königlich Preußischen Hohen Ordens vom Schwarzen Adler (1851), "Von Seiner Majestät dem Könige Friedrich Wilhelm IV. ernannte Ritter" p. 22

- ^ Genealogie ascendante jusqu'au quatrieme degre inclusivement de tous les Rois et Princes de maisons souveraines de l'Europe actuellement vivans [Genealogy up to the fourth degree inclusive of all the Kings and Princes of sovereign houses of Europe currently living] (in French). Bourdeaux: Frederic Guillaume Birnstiel. 1768. p. 109.

Bibliography[edit]

- D. Schedel, Ferencz (1847). Emlékbeszéd József főherczeg nádor Magyar Academiai pártfogó felett [Eulogy over Archduke Palatine Joseph Patron of the Hungarian Academy] (in Hungarian). Buda. Retrieved 7 July 2022 – via REAL-EOD.

- Domanovszky, Sándor (1944). József nádor élete [The Life of Palatine Joseph]. 1 (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magyar Történelmi Társulat. Retrieved 7 July 2022 – via Hungaricana.

- Lestyán, Sándor (1943). József nádor. Egy alkotó élet irásban és képben. 1776–1847 [Palatine Joseph. A Creative Life in Writing and Pictures. 1776–1846] (PDF) (in Hungarian). Budapest: Posner Grafikai Műintézet Részvénytársaság. Retrieved 10 July 2022 – via Magyar Elektronikus Könyvtár.

- Massie, Suzanne (1990). "First Years". Pavlovsk: The Life of a Russian Palace. Hodder and Stoughton. ISBN 0-340-48790-9. Retrieved 8 July 2022 – via Internet Archive.

External links[edit]

- 1776 births

- 1847 deaths

- Sons of emperors

- Austrian princes

- House of Habsburg-Lorraine

- Palatines of Hungary

- Knights of the Golden Fleece of Austria

- Grand Crosses of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary

- Members of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences

- Generals of the Holy Roman Empire

- Burials at Palatinal Crypt

- Children of Leopold II, Holy Roman Emperor

- Sons of kings

- 19th-century archdukes of Austria